There is a dream unfolding in Africa, and in January a group of us from around the world were lucky enough to fly into it.

The plane dropped onto the steaming tarmac at Yoff at two a.m. and we stepped out into the deep dense heat of the sub-Sahara African night. Air, moist with the tang of manioc, salt sea and goat dung wrapped around us as we made our way to the terminal, and into a week that would unfold as one of the most unforgettable conference experiences ever.

The plane dropped onto the steaming tarmac at Yoff at two a.m. and we stepped out into the deep dense heat of the sub-Sahara African night. Air, moist with the tang of manioc, salt sea and goat dung wrapped around us as we made our way to the terminal, and into a week that would unfold as one of the most unforgettable conference experiences ever.

The event was the Third International EcoCity Conference in Senegal, West Africa. There, on the outskirts of Dakar, seventy of us from thirty countries around the globe would understand for the first time what the concept of the “ecocity” is all about.

We would understand it because we would live it. We would be welcomed into the rich culture and vibrant lives of a warm and open people. We would sleep on mats on the floors of village homes that have sheltered the same family lineages for over five hundred years. We would eat rice and manioc and fish from communal bowls with our right hands, and learn to carefully use or left for a less savory, albeit natural, function.

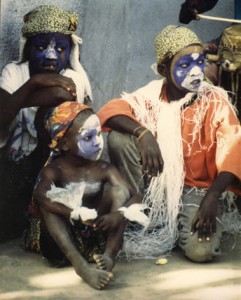

We would see a community that has traditionally lived in harmony with nature instead of in competition with it. A community where cooperation for the betterment of the whole has always been a given, and where governance has for centuries been based on consensus decision making and the idea that all should participate. And despite the cultural, political and social upheaval that pervades African nations and the entire world today, the people of Yoff continue to do what many of us in the rest of the world only dream of.

Sounds unbelievable, this village with its streets of sand, filled with meandering goats and beautiful children and a gentle people going through their daily lives in deep harmony and spiritual wealth. And, although cash is unfathomably limited, jobs non-existent, waste treatment absent, agricultural land nothing but desert and food scarce – there exists a priceless quality of life. There is a lack of prejudice or racism that amazed even fellow Africans. Instead, a self reliance and abundance of cooperation and peace make this village exceptional. This is a place where thirty thousand people can live in one square mile, with no police force – nor any need for one.

It is a place where its seven quartiers each own collective fishing gear and daily rotate responsibility for setting the communal net. Any resident can take part and receive equal portion of the returns. This way, in this job-scarce land, no one goes hungry.

The question for Yoff is – can this continue?

How does a village like this move into the mysterious future of the twenty-first century and claim the best that has to offer while hauling the best of its own past along with it?

How does it cope with the disorientation in cultural and social values that Desperate housewives and Family guy bring sizzling across recently installed electric wires to the most remote village compounds?

How too, does it emerge whole and sustainable in the face of political pressures of a “modern” Senegalese government and the environmental degradation of an encroaching capital city, Dakar?

This is what the Third International EcoCity Conference was all about. It brought people from around the world armed with their workable twenty first century ecovillage technologies and concepts to the very doorstep of Yoff, to be melded with the Senegalese expertise and traditional ecovillage concepts that the villagers have lived with for hundreds of years.

They came to examine the above questions, and contribute to the creation of an ecovillage expansion of Yoff’s crowded current boundaries that will combine the best of new thinking with the best of old ways.

The conference was spawned by Yoff native Serigne Mbaye Diene and Ithaca Eco Village leader Joan Bokaer, who came together during Diene’s studies at Cornell University. Diene’s group APECSY (Association for the Economic, Cultural and Social Promotion of Yoff) hosted the event, and Bokaer’s group brought expertise from around the world and melded it with that of Senagal’s own experts and the inherent wealth of Yoff’s tradition. The outsiders came loaded with concepts and ideas, and from their realm the villagers offered their share with more than equal measure.

In a place where food is scarce, and housing dramatically limited, the whole village responded. Residents of each of Yoff’s seven quartiers were involved in all the major organizational tasks. Responsibility for each day’s lunch and dinner rotated among the seven neighbourhoods, where women of each in turn cooked collectively and transported the food to the main dining hall.

Interest in the event spread quickly to Yoff’s two neighbouring traditional fishing villages. Ngor and Quakam, which also played an active part. By opening day of the conference, every one of Senegal’s coastal villages had sent delegates.

In Yoff the village literally opened its arms to the world, and the world embraced it. Into homes in all quartiers landed citizens of every part of the globe. People from places that were only words on a map (Russia, Australia, Chile, Spain, Canada, Brazil, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, South Africa, United States, Malaysia, and Great Britain) cruised the streets and soon became familiar faces. Children could be heard calling out names from Venezuela, Zaire, Italy, Toga, France, Poland, and China as they clung to the visitor’s hands and tagged along.

This is a grand richness to have people from all countries living with us. I feel that today Yoff is the world, magnifying the fact that we are all one family,” said Diene, as he watched the event unfold.

Hosting in this manner gave the villagers a chance to see people f rom the outside come and respect their traditions, and give credence to the fact that these ways are of incredible value and worth holding onto – a point of view that tends to get lost in the infiltration of consumer oriented Western values.

“From this conference our villagers have gained a new sense of who we are, in addition to some very concrete projects,” said Diene.

This kind of organization and stewardship has also given APECSY an increased presence in the eyes of Senegal’s political authorities. The Mayor of Dakar, who officially opened the conference, was shocked when he learned that people from all these different nations wanted to stay in the homes of Yoff, rather than Dakar’s major hotels. “Incredible,” he said.

This drawing together of our villages has given political authorities an awareness of what we the people can do, and I feel we are setting a precedent for national conferences,” said Diene. The impact of this grass roots effort at both national and international levels was also extremely important because of its consequences in terms of development – both in Yoff, and throughout Africa.

To get a better idea of the role this conference played in the lives of its participangs and its host village, and why the total package was an environmentalist’s/ecologist’s/international developer’s dream, a little history is warranted.

Yoff was settled by the people of the Lebou tribe who migrated from Ethiopia, and for centuries operated a democratic system akin to a modern republic. Their system was so well-respected they were essentially left alone, even through colonization. They were also self-sufficient, with expert fishermen and farmers producing millet, maize, manioc and a variety of vegetables, fish and milk in abundance.

This lasted until well into the 1970s when the political upheaval that followed Senegal’s independence brought mass urbanization, a population boom, and an environmental crisis. “Nothing in Yoff’s experience prepared it for this,” said Diene.

It was at that time Yoff’s traditional leaders unintentionally signed away the village’s agricultural land to the newly independent government for the expansion of Dakar. Now highways, a convention centre, and the country’s main airport occupy land once farmed and grazed by villagers. One hundred fifty acres of that remained undeveloped, and was left to lie, quickly reverting back to desert.

A small group of highly educated young people, led by Diene and aware of the Senegalese government threat to their survival, formed APECSY. Their intention was to bring together Yoff’s diverse forces, and advocate for the best interests of the village regarding development, administration, and the economic sector, and to preserve the cultural heritage and values of generations.

They succeeded in this because of the non-aggressive way they wove their function into the gerontocracy. “Yoff yesterday and today,” is their mode of operation, rooted in tradition. “The elders were skeptical at first, but now we have an organization that is formally accepted by both government and elders, and has the corresponding legal and political power, and recognition,” he said.

The formation of APECSY added a nonthreatening “modern” layer to the traditional elders’ governing structure, creating a process more fully prepared to handle the changing Senegalese world. Over its fifteen year existence it has successfully woven participation of younger men and women (under 55 years of age) into the decision making process.

Since it began APECSY has: created a vegetable farm run by a women’s cooperative; established its own Credit Union allowing cooperatives and entrepreneurs to receive start-up and expansion loans; created a health centre for people not covered by employee health insurance; and established a family-supported local health insurance program. APECSY’s Fishermen’s Union is organizing fishermen throughout the region, and has built a sports field on a tract of land gained back from the city of Dakar. They have also built an elementary school; villagers carried seventy percent of the cost by each contributing one home-made brick or its equivalent.

Recently, APECSY logged its most phenomenal success when it officially reclaimed one hundred and fifteen acres of the expropriated former agricultural land that is so crucial to Yoff’s continuing survival. Here, on this land, an ecovillage will be built. The land, now desert, will become an extension of the existing village, which has recently almost doubled its population as the capital city of Dakar expands into it. On this virgin territory, the ecovillage will address Yoff’s urgent needs for housing, waste treatment (currently non-existent), health, and cultural survival.

Robert Gilmen is co-founder of the Context Institute. His definition of an ecovillage is a good one in relation to the Yoff extension. He describes it as “a human-scale, full featured settlement in which human activities are harmlessly integrated into the natural world in a way that is supportive of healthy human development and can be successfully continued into the indefinite.”

The Yoff extension will include culturally appropriate housing, intensive urban agriculture, biological sewage treatment, and renewable energy sources in a way that marries easily with the existing village. Key to the success of this project, (and the first thing to be built), will be an EcoCentre that will work on developing and demonstrating sustainable solutions to local problems. John Katz of Ithaca, New York has worked closely with the APECSY group on this project. He said in order to implement a complex innovation such as an ecovillage they will first create the EcoCentre to introduce approaches, then test them and adapt them to local conditions before incorporating into the larger extension design.

This EcoCentre will be built in the most accessible and visible region of the reclaimed land so it can be seen from the main highway. It will address local, national and international education interests. The municipality of Dakar and the University of Dakar are already actively involved. An adjunct to the EcoCentre called EcoPole is also being considered. It will house a sustainable technology educational institution with classrooms, conference and residential facilities.

The Third Annual EcoCity Conference brought all these into focus and more. It pulled the worldwide expertise of participants (all of whom paid their own fares) to its doorstep. Their areas of knowledge covered everything from ecologically sensitive land use, appropriate technology, and architectural design, to rural planning and food technology. Lecture halls filled to capacity every day for talks on resource conservation, sustainable agriculture and development, land restoration, or waste treatment and disposal. And brilliant discussions like that of social anthropologist Tukumbi Lumumba Kasonga analyzed the politics, economics and philosophy of the subject matter.

Throughout the eight-day conference in Yoff, impromptu nightly gatherings saw tremendous exchanges between visiting experts and their Senegalese counterparts that were non-aggressive and vastly productive. Ideas were thrown into the arena, thrashed apart and accepted or discarded accordingly to options and local conditions.

By the end of the conference, nutritional scientist and Tufts University professor Marion Zeitlin had transferred an outstanding multi-faceted development project (originally intended for Nigeria) to Yoff, to be dovetailed with the ecovillage expansion. It will, among other things, create a sustainable food security research site staffed by local people growing food products that contribute to a nutritionally balanced diet. Interest in this project is phenomenal and worldwide.

The hope of all is that the benefits of this extraordinary conference will ultimately reach beyond the borders of Senegal, and into the rest of Africa. This may well be the most elusive task.

For those of us who came to Africa and into the lives of Yoff, the experience was unparalleled. Richard Register of Berkeley, California, who convened the first EcoCity Conference back in 1990, and who now shoulders the bold title Father of the EcoCity Movement, spoke for all of us when he said: “People of Yoff, I have never in my life been so warmly received by anyone, anywhere. Thank you for the gift of this memory which I will carry for the rest of my life.”